Sarah Fukami

/Printmaker Sarah Fukami, a young woman of Japanese, Italian, and Polish decent, waved me over for our meeting while I was browsing the work currently on view at Art Gym Denver. Quietly setting out her prints for me, I watch as each delicate, multi-layered print is pulled out from a mylar sleeve and carefully placed on top of the mylar sleeve to be viewed. Though I had seen Fukami’s work before this point, never had I sought out the content behind these visually compelling pieces of work, and as we slowly began to unpack the content and intention behind each print, while speaking across from each other with the work in the middle, I was rendered speechless so many times. This was one of those interviews where all you can really say is, ‘yeah……’ and ‘…..wow…..’ while trying to grasp what you have just been told, but still trying to drive a conversation

Go seek out a chat with Sarah Fukami, it will be well worth your time.

Though I will try my best, I don’t think I will even begin to scratch the surface of the work that goes into each print.

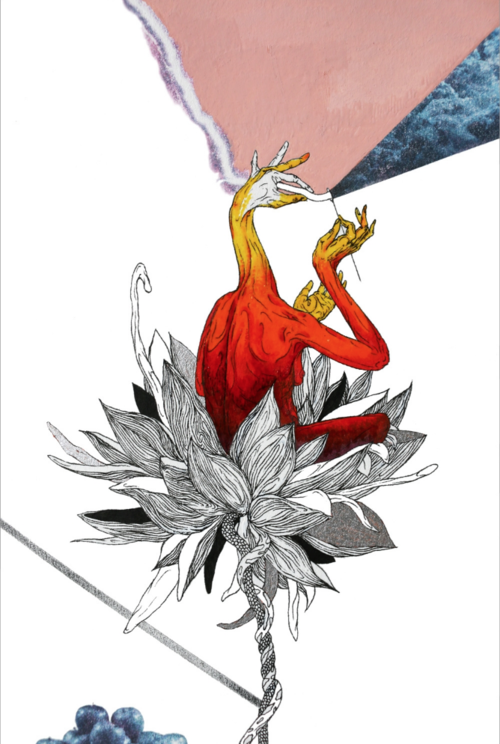

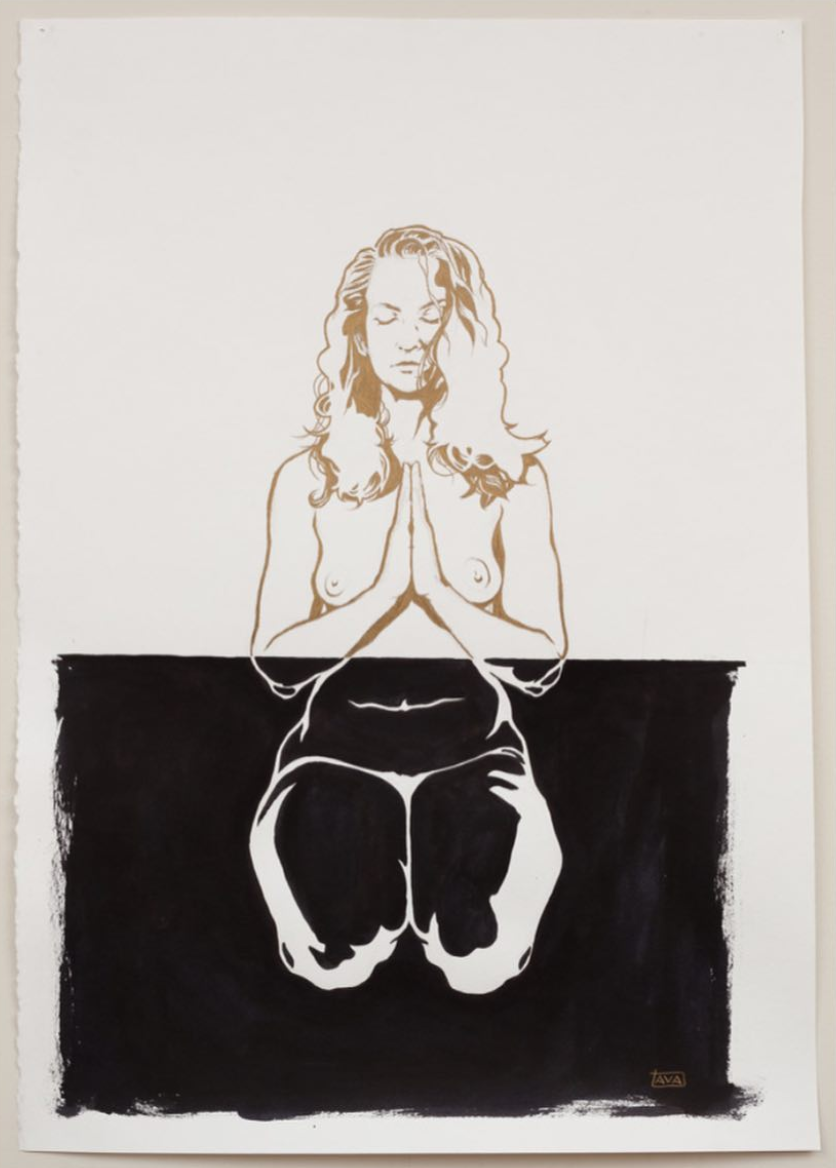

Original Art Work by Sarah Fukami. Image courtesy of the artist.

Based in Denver, CO, Sarah Fukami grew up in a multicultural family and really found a home with the Japanese part of her heritage. She was raised hearing stories: “When I was young they would always talk about ‘camp’ and when I was really young I didn’t really get that, but that’s kind of the way they talked about it … They always wanted us to know what happened, and remember that it happened, but never in a negative way. They really view it as just something that happened and they’re better for it, they overcame.”

What Fukami is referring to is something many of Americans have no idea about, including myself going into this interview, which is the Japanese interment in America following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Fukami told me that, “75% of the people that I talk to know little to nothing about internment… and it’s not really your fault, because the way that education is organized they just kind of pass over it,” which in a political climate of exclusion and segregation of ‘othered’ bodies, is something we really need to revisit.

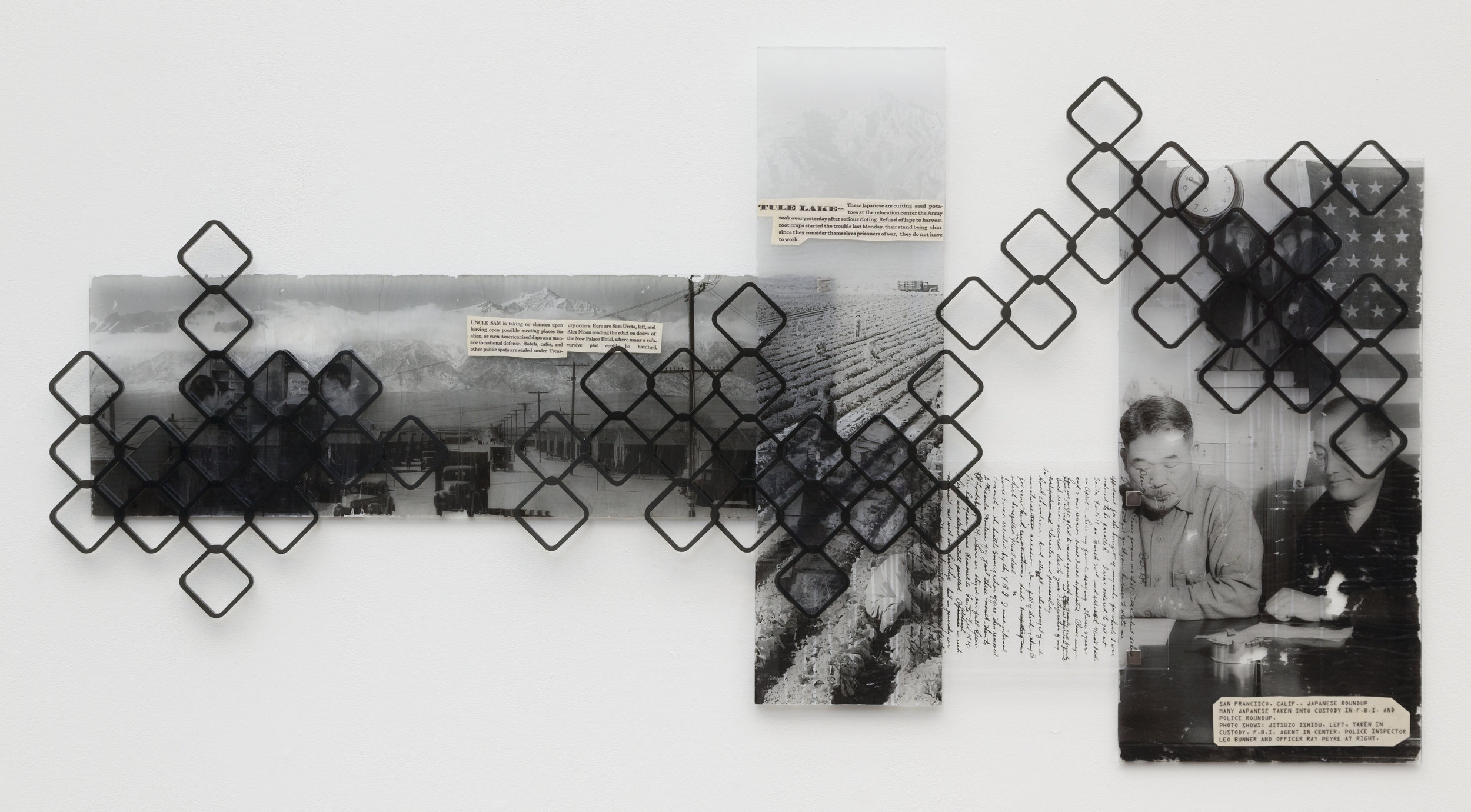

Ansel Adams Photograph of Japanese Internment Camp. Image from Library on Congress database.

Japanese internment began when Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which started the process of relocating anyone of Japanese ancestry, including Japanese-Americans born as American citizens, to internment camps. “I really want to reach outside of my own family experience and get to that greater understanding of ‘what does it mean to be an immigrant?’ I think that is particularly interesting for Japanese-Americans, especially first generation who come to America, and they want to be American, and then all of a sudden everyone just turns on them and says ‘You’re not American, we’re afraid of you, we’re going to send you into the deserts of America for two to three years.’ What does that do to your identity? Your national identity as an American?”

This imprisonment lasted for three years from 1942 to 1945 when the citizens were released, having to completely remake their lives. All possessions of the interned were gone because “they could only have what they could carry … they had to sell everything off at crazy discounts just to get rid of these things, and then when they got out there was nothing left.” Luckily for Fukami, family photographs and documents were some of the possessions that were carried with her family, as without those documents her work may have never been made. For Fukami “it all started by investigating my great grandfather … I basically just went through my family’s basement in Chicago and opened trunks and looked through documents and found these things.”

Through investigation and material exploration, Fukami began the process of image transfer on Plexiglas, as well as laser cutting into said Plexiglas, which was the first time that photography began to weave its way into her work.

"Wake Me". Image courtesy of the artist.

“I fell in love with the process of reproducing photographs and then adding to them … I’m all about the preservation of the image itself … I was always really scared to use my own family photos, which got me started [thinking] how can I reproduce this and then do something with it?”

Fukami’s current works stems from this idea of reproduction and most importantly reinterpretation. Her primary source of imagery comes from portraiture photography used for Japanese internment propaganda, taken by renowned photographer Ansel Adams. Adams was commissioned by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to create this body of work. “One of their main goals was to convince the American people that this was okay, that this was acceptable … and they relied heavily on propaganda for that.

Ansel Adams Photograph of Japanese Internment Camp. Image from Library on Congress database.

They [the photos] are very much the white male gaze … [Adams] was in such a position of privilege … he totally meant well, don’t get me wrong.”

We began speaking on this subject and Fukami expressed some hesitation, saying “he wanted to really show the goodness in Japanese people, which I appreciate, but at the same time, you know…”

I finished her sentence, saying, “They were just not used in the right way,” to which she replied, “…yeah” with a sigh.

This body of work, which is around 200-300 photographs, with nearly half being portraits, was later exhibited in a show titled “Born Free and Equal” and the body of photos was donated to the Library of Congress without any restrictions, meaning the work is open source and readily available.

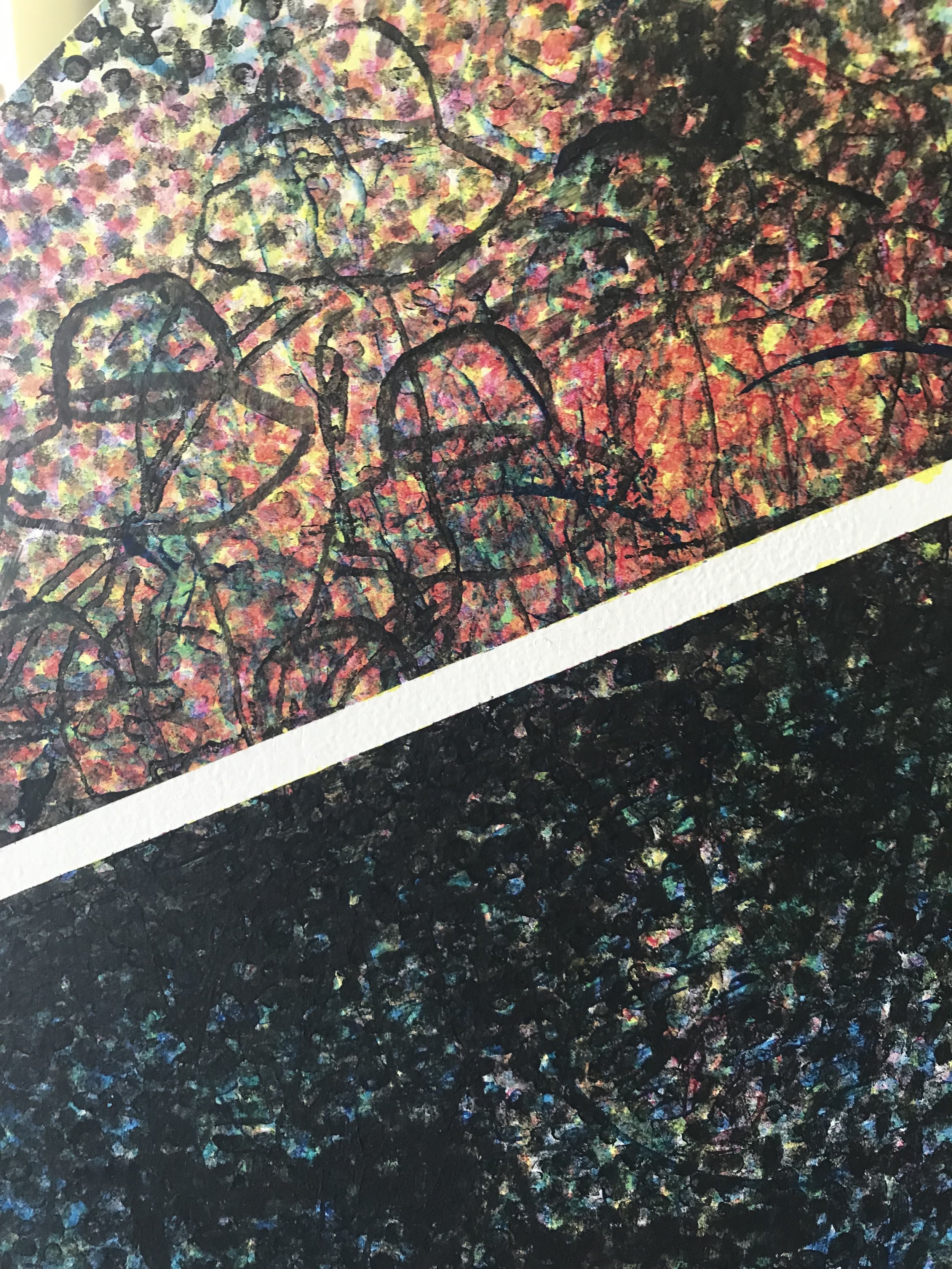

Original prints by Sarah Fukami. Image courtesy of the artist.

Among these photos are also classic Ansel Adams landscapes, but depict the sites of internment, which Fukami has begun tapping into as well. “It’s a really crazy juxtaposition when you see landscapes like this, because you look at it and want to say, ‘Oh, that’s really nice’ and what I want to do with my work is make you take a second and think, ‘Wait a minute, what’s happening here?’”

This idea of trapping and realization from the viewer is something that runs through all of Fukami’s recent work. She told me she wants to “trap the viewer with the beauty of the photograph and the pattern and the color and then get them to take a second and think about how relevant this is, even right now.”

"The purpose of them visually is to draw the viewer in.”

Installation view of "Across the Ocean, Over the Wall" completed as resident artist at PlatteForum. Image courtesy of the artist.

In addition to the sourced photography Fukami layers her prints with colorful screen printed patterns, as well as laser cut etchings. Her colored screen prints are highly pattern driven, deriving her imagery from traditional Japanese wood block prints used to create textiles for kimonos or other decorative fabrics.

Though the colors and patterns don’t have direct contextual meaning or place, they serve a function of drawing the viewer in. “They serve to intrigue the viewer from a distance … and then when you get close … that’s what I love about the laser cutting...”

"I love the process,

and then I love to thwart the process."

The last layer of her prints are laser cut alphanumeric codes that she pulls from a national database of interned Japanese-Americans. Similar to the effect of Jewish catalogs during Nazi Germany, this database is broken into categories for information about each interned citizen. Mining this type of document, Fukami described the visual aspect of the list as ‘jarring’ while also difficult as her family is included as well, though has bypassed this difficulty, choosing to tattoo her family’s number on her body as “an act of remembrance”. These codes were an instant addition to her prints when she found them, and through laser cutting, Fukami has found a way to implement them in a content heavy way.

“That’s what I love about the laser cutting … it’s physically taking away from the print … pieces are gone, it’s burning into it … and to me that’s very profound.” She views the original function of the codes as a method to stereotype and “fit these people into boxes, to make them into symbols or numbers, when they’re just people.” Fukami has embraced this idea, now contrasting this terrible notion of degrading people down to a number with stunning portraits of joyous Japanese-Americans and with striking patterns in bright colors. She states, “it’s light hearted imagery, beautiful patterns and colors, and then this burnt, black and white representation of them.”

"Across the Ocean, Over the Wall (detail)". Completed as resident artist at PlatteForum. Image courtesy of the artist.

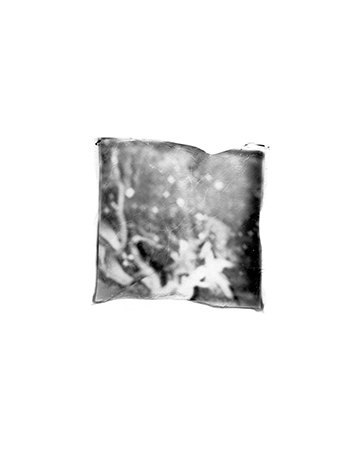

Because of the nature of cutting paper, occasionally pieces of her prints will fall away and be swept up. She spoke on this aspect of display saying, “that’s very representative of my process … it’s all about history and memory and what happens to that over time? It degrades, it becomes blurry, it becomes forgotten, it becomes pieced together, and that’s what these processes are like for me. … [they’re] layers on layers on layers [and] it’s me meditating on that. It’s all about me honoring that individual like they were my family.”

Her newest exploration with this process begins with thicker paper, and rather than laser cutting from the front, she has begun to laser cut her codes, as well as her patterns, from the back. This new technique allows for light to activate the print and has potential for more complex visual layering within her work.

Fukami showing her newest iteration of laser cut prints. Image by Drew Austin

My eyes were opened to a whole historical period that I never knew about during my hour spent with Sarah Fukami, and her work went from simply visually interesting, to conceptually powerful and moving as well as visually stunning for me. Fukami’s work can currently be seen in Redline’s 10X Anniversary exhibition as well as at Alto Gallery starting March 22nd for Month of Printmaking. She will also have a piece in "Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms/Reimagining the Four Freedoms" a traveling exhibition beginning at the New York Historical Society May 25th, and ending at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA November 2020, hitting five national and international venues in between. More of her work can be seen via her website, as well as her Instagram page.