Sukha Worob

/The historical canon of printmaking runs deep.

A practice of meticulous detail and clean execution, printmaking has been defined by icons throughout the years; Albrect Durer’s detailed woodcuts, Rembrandt’s gorgeously lyrical etchings, and Hokusai’s multi-colored The Great Wave (or Under the Wave off Kanagawa). This art form has been through many different rebirths and manipulations, being reclaimed through screen prints by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenburg, and now being taken to the streets via wheatpaste by artists like Swoon.

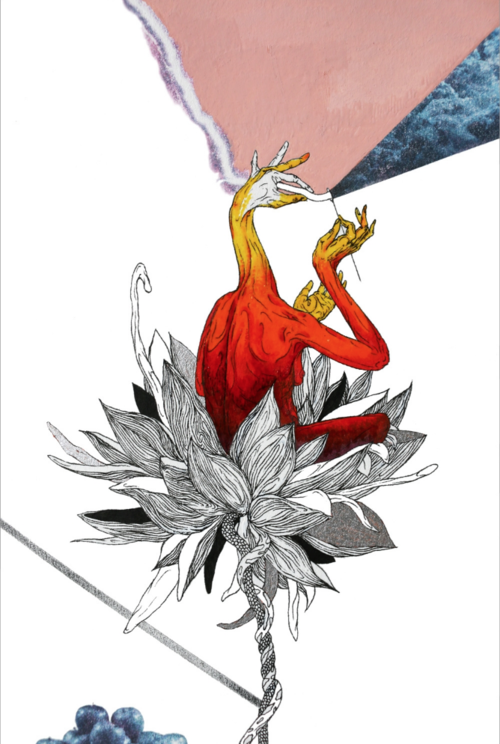

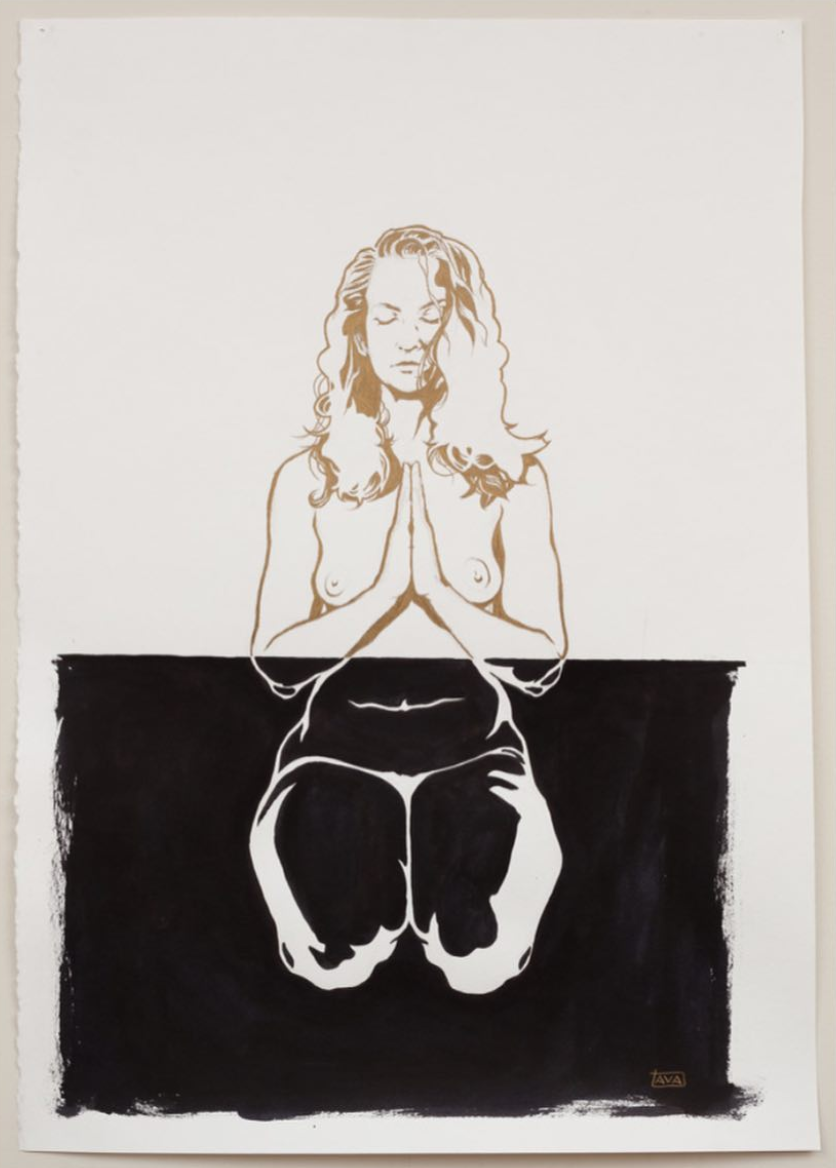

Prints on Paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

And yet there is still room for reinvention in the mind of Bozeman, MT based artist Sukha Worob, who has allowed for the tightly controlled medium to move into the hands of the public.

Born in an Arizona commune to a teacher and an artist, Worob was raised with the idea of community all around him. Created by Russian artist Louis Lozowick, the commune existed around the ideals found in Eastern Philosophy, and the subconscious influence from Lozowick is an interesting connection throughout Worob’s life. As a child he was invited often to draw on the desk of this astonishing artist, who is known for dense, rich drawings and prints on paper, shown around the world and in the collections of esteemed institutions such as The Metropolitan Musuem of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, Walker Arts Center, and the Whitney, only naming a few. Though I am sure his parents were aware of this influence, the young boy drawing at Lozowick’s desk was unable to comprehend the importance of this man until much later in life.

Worob printing during a workshop at the Bend Art Center. Image courtesy of the artist.

Not intending to follow in his parent’s career path, Worob attended the Northern Arizona University as a math major, quickly flipping between French studies, anthropology, and education before ending up in the printmaking studio. The idea of problem solving is the vein that runs through it all, and as artists often do before making their own work, Worob sought out realistic ways to make a living as a problem solver, but ended up trapped by the energy that comes with printmaking.

This place of creation held a certain energy that Worob instantly felt at home with. The studio was a melting pot for language and technology where he was able to integrate his fascination with mathematics into the instructional nature of making a print. And the cherry on the top of it all: community.

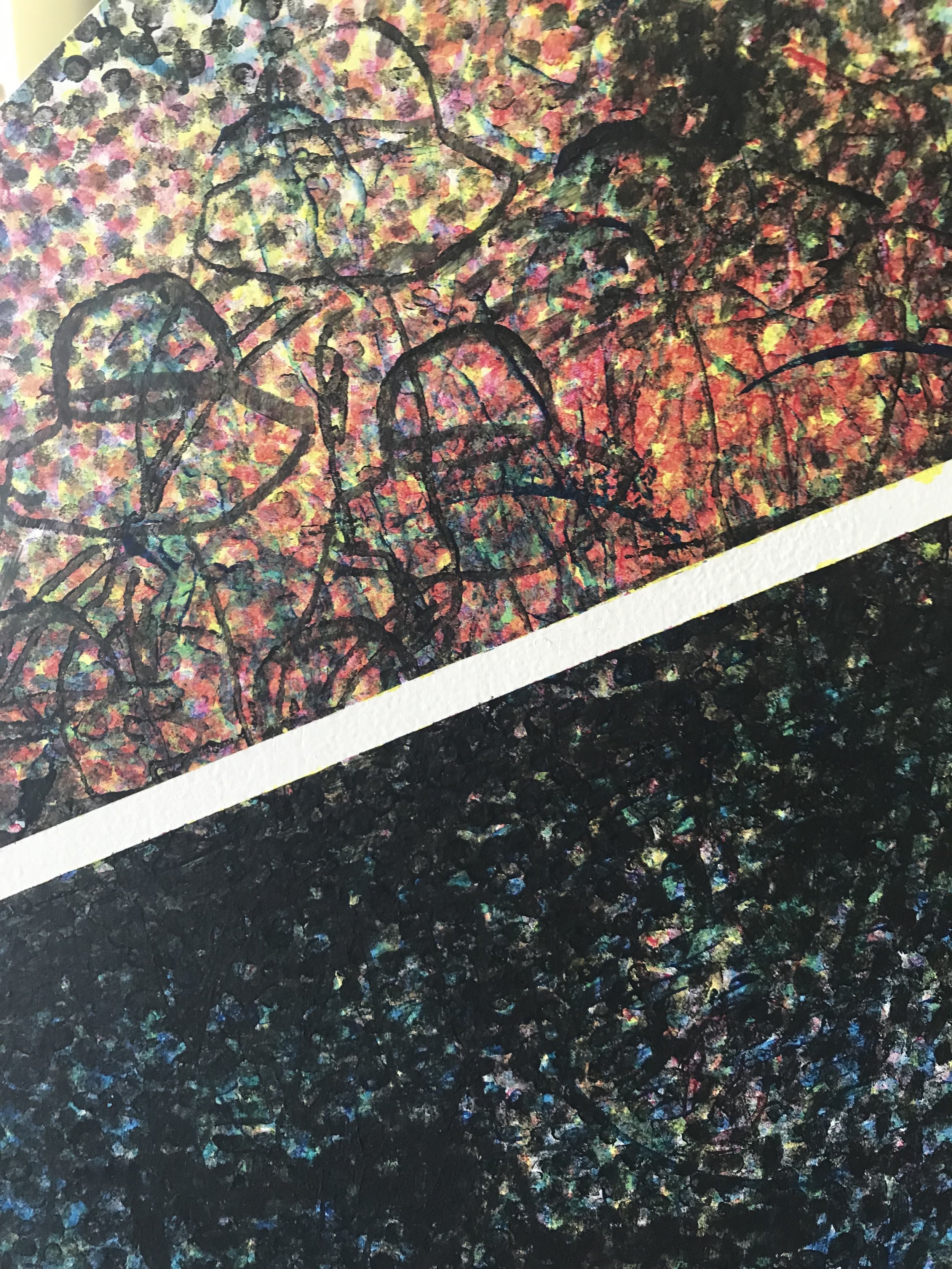

Detail from It's Crowded in Space, collaboration with Andrew Rice. Image courtesy of the artist.

Worob recounted to me stories of late nights in the printmaking studio with his friends. These late nights grew his love for the medium and expanded his thinking of what potential a community could hold. This class, known for being the worst class his professor has ever taught, were prolific with their work, staying up all night before cleaning up quickly before class started again the next morning. The studio became their home base and planted a seed which began to grow quickly for Worob after graduation.

Flipping between majors and interests in undergrad, he sought out further education more as a commitment to himself rather than a means to make a living. He believes that there is still some room to change directions after undergrad, but a master’s degree means you are all in, and so Worob began along his path as a printmaker and attended Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana, where he still resides.

Now known for the way he pushes the idea of a print matrix, Worob stumbled upon his iconic tools only through trying to escape the pressures of his thesis in grad school. He turned to the woodshop as a sort of refuge from his printmaking work, but ended up solving one of his biggest problems while doing it.

Attempting to create a method of printing that could relay a large amount of content in a cheap and manageable way, Worob began creating large rollers and print rockers, which he still uses today.

To grasp what these tools are, think about the classic rolling pin you can find in any kitchen. Extend the handles out, and expand the cylindrical form from a 2” diameter to a 12”-15” diameter and you can begin to understand the massive scale of Worob’s unique print matrices*. The rollers are then covered in his imagery, currently scatters of off-circle dots and the broken letter forms of his Zamenhof’s Trials body of work, which are created using a silicon molding process, resulting in a positive relief which gets wrapped around the rollers.

For those who aren’t trained in the arts or if those terms just went over your head, imagine a hand-made foam roller with custom designed markings that stick out from the cylindrical foundation, but with handles.

Participant printing with Worob's homemade print rollers. Image courtesy of the artist.

These tools, often cumbersome for viewers and confusing upon first glance, are an essential part of Worob’s process, allowing him to print directly onto wood panels and walls, covering large amounts of space extremely quickly and with chance encounters coming up often.

Working around the idea of potential, meaning the chance that something could randomly happen through the process of printing, Worob now creates the tools and often gives the actual printing of the work over to his audience. As a self-proclaimed control freak the action of giving over the visual side of his work to the audience was nerve-wracking, which is why he turned towards it so hard. Giving the power to the viewers put him outside of his comfort zone, and allowed him to understand that his power existed more in the creation of the tools and the subtle direction he is able to give the viewers.

Often during exhibitions Worob will stand back from the crowd, watching the print come to life before his eyes, and will step in to add a few marks where needed, which pushes the viewers in a different direction and allows for Worob’s vision to come through more clearly.

Image courtesy of the artist.

The ideas of control and struggle often arise for me when thinking about these community gatherings of people creating Worob’s work. The tools he creates are suited perfectly for him and the way he handles them is fluid and exacting, but when you hand them to a viewer they are instantly paralyzed, trying to figure out the correct way to use them.

“I love the idea that when there’s the right mix of people and the right mix of motivations, that something amazing can happen.”

Worob is a gutsy artist to say the least, quite literally making a career for himself out of others making his work. I mean this in the best, non-Warholian way. He brings people together, gives them the materials and slight suggestion, and accepts what others create as his own. He is a master of playing with the idea of potential and what that can unfold into: the potential for an act to happen, for a mark to be out of place, and the potential for what can be a printmaking matrix.

I am often drawn back to Robert Rauschenberg and his idea that if something could be make a mark on a lithography stone, then it could become a printed image. His process was experimental and he truly pushed the boundaries of a medium, something that I believe Worob is doing with printmaking in a contemporary context.

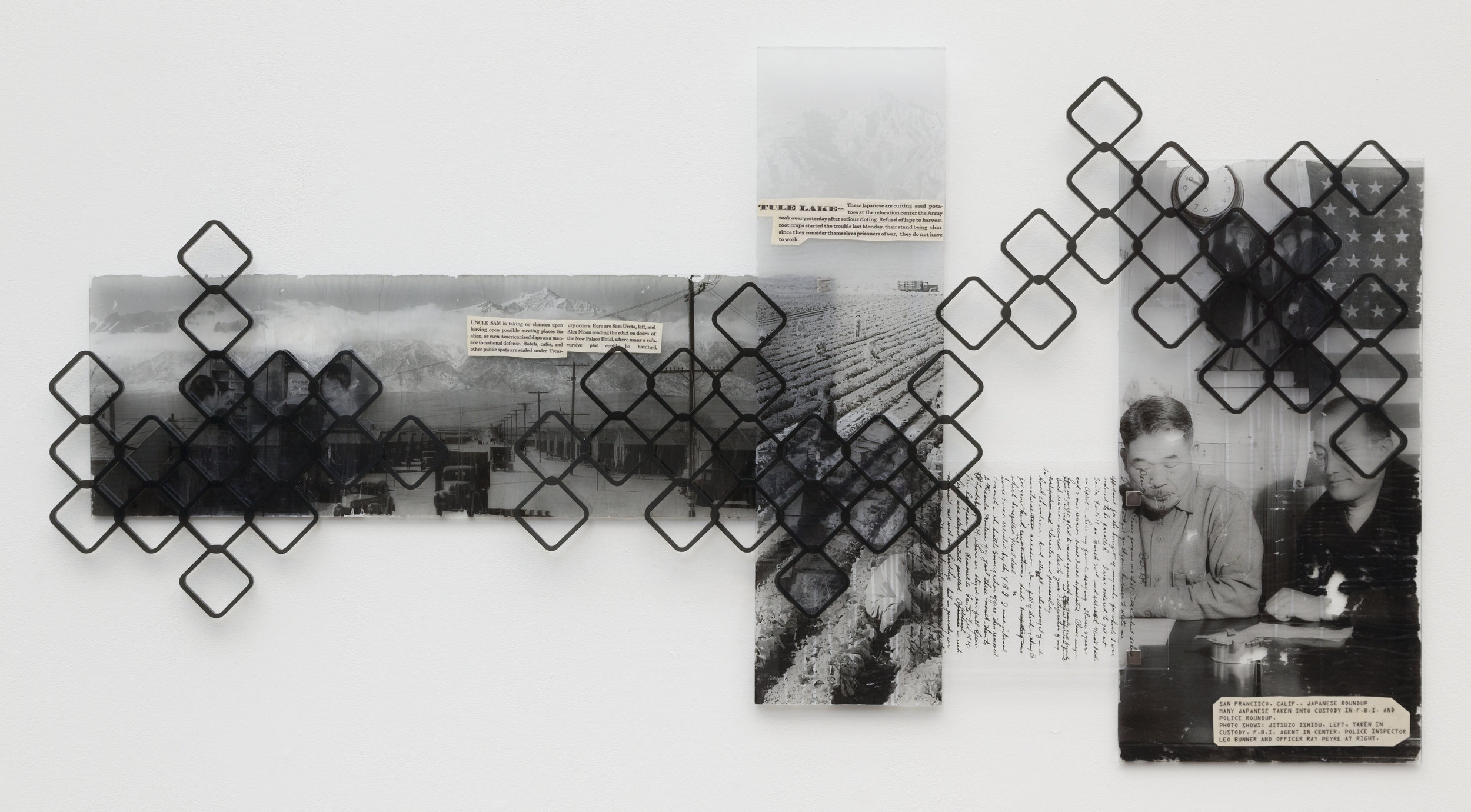

Installation view from Bend Art Center. Image courtesy of the artist.

As a printmaker, an educator, and a father Worob does not have a lot of time, though based on his recent exhibition record you would think otherwise.

A feeling of guilt constantly sits in his stomach, wishing he had more moments to dedicate to his two children, and feeling selfish almost 100% of the time. Both his wife and himself are ‘professional parents’ and while this can be great for a child to see, they both regret time not spent with their family.

This being said, when I spoke to Worob specifically about being a father, he had one of the most amazing responses I have ever heard. He often will invite his children into the studio with him while he works and he never delineates what is his and what is theirs. Everything is free game, which includes expensive paper, inks, nice drawing tools, and more, never giving his children their own set of low-quality drawing tools to use, but rather letting them use the exact tools that he himself uses. He told me one of his own prints in his collection at home recently got the addition of collaged apples, and that he loved the change.

Install shot from It's Crowded in Space, collaboration with Andrew Rice. Image courtesy of the artist.

Though not completely satisfied with it, he has managed to find a balance between being a teacher, a constantly exhibiting fine artist, and a father as well as a husband.

Influenced through his children’s use of color and form, Sukha Worob’s work is beginning to find more color and beginning to grow more experimental in installation as well. A community man at heart, his children fuel his community at home, with strangers and collaborators filling those holes back in the gallery.

Worob’s work can be found on his website and on his Instagram profile. He is currently exhibiting with the Missoula Art Museum, Emmerson Center for Arts and Culture, Holter Museum of Art in collaboration with Andrew Rice, as well as in group shows in Wisconsin and New York

*A print matrix (plural matrices) is whatever the artist uses, with ink, to create an image. This comes most traditionally in the form of an exposed screen, a lithographic stone or plate, or a etched wood/linoleum block.